Our newest paper just came out in the Journal of American Geriatrics Society and shows that across the US, pedestrian fatalities from motor vehicle crashes among older adults cluster around senior centers, community centers, libraries, pharmacies/drug stores, and healthcare/hospital/health services. This work is part of our ongoing research agenda to identify ways to increase pedestrian safety, both for injuries from motor vehicles and for injuries from pedestrian falls.

Walking has a myriad of health benefits and multiple urban planning/design guidelines emphasize creating built environments that support pedestrian activity. However, concerns around pedestrian safety, from cars and from falls, are a barrier to walking, particularly for older adults. Older pedestrians experience the highest death rates in traffic crashes compared to any other age group, and yet there are no national policies or programs that focus on the making the pedestrian environment safer for this vulnerable group.

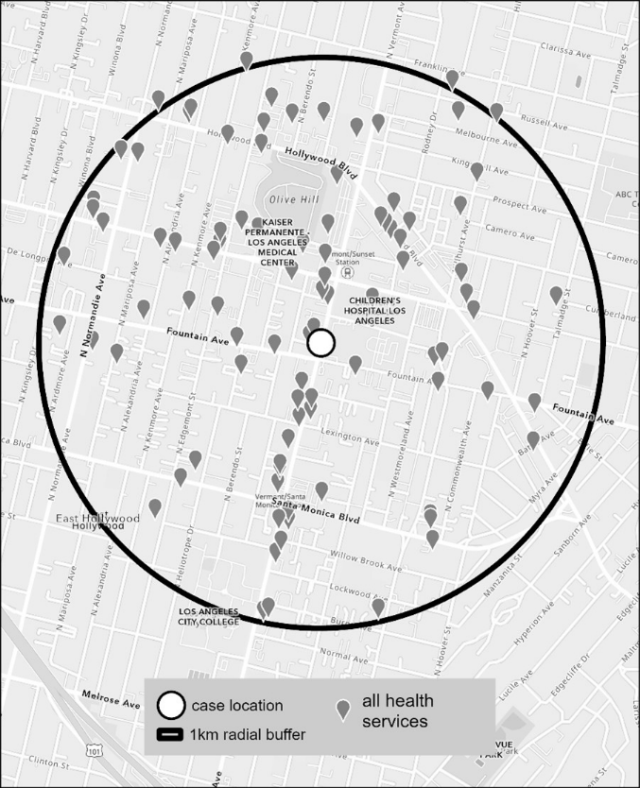

The research first involved using the NETS data to identify venues older adults frequently walk to or from, and narrowing our list to focus on establishments typically operated by municipalities (e.g., libraries, senior centers) or licensed by city and state governments (e.g., hospitals) – making them attractive partners for government efforts to improve safety. These public establishments were then categorized into two broader categories for the analysis: 1) residential living facilities (assisted living facilities, continuing care retirement communities, and skilled nursing facilities) and 2) walkable destinations for older adults (senior centers, community centers, libraries, pharmacies/drug stores, and healthcare/hospital/health services). We analyzed the density of these two metrics at 10,529 locations where a pedestrian was killed in a motor vehicle crash (case locations) between 2017 and 2018 and at two matched control locations per case location.

Analyses indicated that a higher density of older adult walkable destinations were associated with locations where older adult pedestrians were fatally struck, even after adjustment for the nearby older adult population. For fatalities involving pedestrians age <50 there was no association between these destinations and where pedestrians were killed. But for pedestrians age 50-64 and 65+ a higher density of these destinations was associated with locations where pedestrians were killed, with the strongest associations for pedestrians age 65+. A similar pattern of results was observed for the density of residential facilities.

To the left: health services within 1Km of the location where a pedestrian was killed by a motor vehicle.

The identification of specific high-risk environments for older pedestrians will hopefully spur new investments in evidence-based, cost-effective pedestrian safety interventions in these areas, such as leading pedestrian intervals, pedestrian refuge islands, and crossing signage. The studied destinations, facilities and residential settings are typically operated by municipalities or licensed by city and state governments, and so this work suggests some natural partnerships for improving pedestrian safety. As shown in the Figure from the paper, areas with high concentrations of health care facilities, like city medical centers, may be especially important areas for cities to focus their pedestrian safety efforts to prevent older adult pedestrian injuries.