The Columbia Population Research Center’s Computing and Methods Core has been developing a series of research methods use cases for Large Language Model generative AI tools, largely focusing on ChatGPT-4. Our first case study was just published in JAMA Network Open and assessed whether ChatGPT-4 could extract useful information from unstructured clinical narrative notes in electronic medical records. The short answer was, it depends on the day of the week; across five days of repeated analyses ChatGPT-4 was better at repeating its hallucinations than its accurate work.

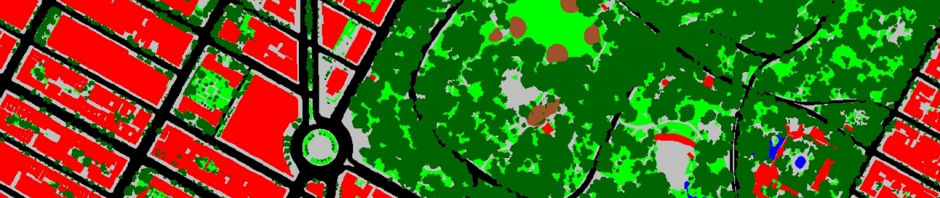

There is a vast amount of medically relevant data within unstructured clinical narrative notes in electronic medical records (EMR) that are not captured in the structured data of medical records. Building on our work on built environment strategies for injury prevention (here and here) we tested whether ChatGPT could read clinical narrative notes and identify whether or not a patient injured in a micromobility accident (e.g. bicycle, scooter) was wearing a helmet. Using deidentified emergency department clinical note data for 54,569 patients from the US Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) database we built a detailed text string search-based approach to identify helmet usage. We then prompted ChatGPT-4 to read the same medical records and identify patients noted as wearing a helmet, noted as not wearing a helmet or patients where no helmet related information was provided in the clinical note.

ChatGPT was only able to replicate the results of the text string search-based approach when the entire text string search strategy was included in the prompt text, when less detailed prompts were used ChatGPT performed poorly. However, a major concern was that when this highly-detailed prompt was used repeatedly, with the same EMR data, in new chat sessions on 5 unique days, ChatGPT did not do a good job of replicating its work. On day 1, ChatGPT’s results closely replicated the results of the text string search-based approach, but on day 2 ChatGPT’s results did not. On days 3 and 4, ChatGPT replicated its inaccurate results from day 2’s analyses, and on day 5 ChatGPT replicated its results from day 1. ChatGPT struggled with negated terms, such as “w/o helmet” or “unhelmeted” or “not wearing a helmet”. For 400 of these medical records, three of the investigators read the clinical notes to create a gold-standard data set of patient helmet use classifications. Using ChatGPT’s results that best replicated the results of the text string search-based approach, ChatGPT’s classifications matched those in the gold standard data set.

ChatGPT-4 could extract useful data from clinical notes, on some days, when prompted with a highly detailed set of text strings to search with. However, a substantial amount of effort was required to generate and test the text strings before using them in the prompts.